Typography is a service art, not a fine art, however pure and elemental the discipline may be.

sometimes more sharpened, sometimes more flattened,

What we find, more or less,

in the art of printing are masterly variations accompanied by technical improvement in the production of the instruments. The same thing happened with a second invention in the visual field—with photography. The moment we stop riding complacently on our high horse, we have to admit that the first daguerreotypes are not primitive rough-and-ready things but the highest achievements in the field of the photographic art. It is shortsighted to think that the machine alone, that is to say, the supplanting of manual processes by mechanical ones, is fundamental to the changing of the appearance and form of things. In the first place it is the consumer who determines the change by his requirements; I refer to the stratum of society that furnishes the “commission.” Today it is not a narrow circle, a thin upper layer, but “All,” the masses.

The idea that moves the masses today is called “materialism,” but what precisely characterizes the present time is dematerialization. An example: correspondence grows, the number of letters increases, the amount of paper written on and material used up swells, then the telephone call relieves the strain. Then comes further growth of the communications network and increase in the volume of communications; then radio eases the burden. The amount of material used is decreasing, we are dematerializing, cumbersome masses of material are being supplanted by released energies. That is the sign of our time. What kind of conclusions can we draw from these observations, with reference to our field of activity?

44

the graphic designer today seems to feel that the typographic means at his disposal have been exhausted. accelerated by the speed of our time, a wish for new excitement is in the air. “new styles” are hopefully expected to appear. nothing is more constructive than to look the facts in the face. what are they? the fact that nothing new has developed in recent decades? the bore-dom of the dead end without signs for a renewal? or is it the realization that a forced change in search of a “new style” can only bring superficial gain?

it seems appropriate at this point to recall the essence of statements made by progressive typographers of the 1920s:

previously used largely as a medium for making language visible, typographic material was discovered to have distinctive optical properties of its own, pointing toward specifically typographic expression. typographers envisioned possibilities of deeper visual experiences from a new exploitation of the typographic material itself.

typography was for the first time seen not as an isolated discipline and technique, but in context with the ever-widening visual experiences that the picture symbol, photo, film, and television brought.

they recognized that in all human endeavors a technology had adjusted to man’s demands; while no marked change or improvement had taken place in man’s most profound invention, printing-writing, since gutenberg.

the manual skill and approach of the craftsman was seen to be inevitably replaced by mechanical techniques.

once more it became clear that typography is not self-expression within predetermined aesthetics, but that it is conditioned by the message it visualizes.

that typographic aesthetics were not stressed in these statements does not mean a lack of concern with them. but it appears that the searching went beyond surface effects into underlying strata. it is a fallacy to believe that styles can be created as easily and as often as fashions change. more is involved than trends of taste devoid of inner substance and structure, applied as cultural sugar-coating.

moreover, the typographic revolution was not an isolated event but went hand in hand with a new social, political consciousness and, consequently, with the building of new cultural foundations. the artist’s acceptance of the machine as a tool for mass production has had its impression on aesthetic concepts. since then an age of science has come upon us, and the artist has been moti- vated more than ever to open his mind to the new forces that shape our lives.

new concepts will not grow on mere design variations of long-established forms such as the book. the aesthetic restraint that limits the development of the book must finally be overcome, and new ideas must logically be deduced from the function of typography and its carriers. although i realize how deeply anchored in tradition and how petrified the subject of writing and spelling is, a new typography will be bound to an alphabet that corresponds to the demands of an age of science. it must, unfortunately, be remembered that we live in a time of great ignorance and lack of concern with the alphabet, writing, and typography. with nostalgia we hear of times when literate people had knowl-edge, respect, and understanding of the subject. common man today has no opinion at all in such matters. it has come to a state where even the typesetter, the original typographer, as well as the printer, has lost this culture. responsi- bility has been shifted onto the shoulders of the designer almost exclusively.

in the united states the art of typography, book design, visual commun- ication at large, in its many aspects, is being shelved as a minor art. it has no adequate place of recognition in our institutions of culture. the graphic designer is designated with the minimizing term “commercial” and is generally ignored as compared to the prominence accorded by the press to architecture and the “fine arts.” visual communication has made revolutionary strides and real contributions to the contemporary world picture. yet, the artist-typographer represents a small number of typography producers compared to the output of the nation. their efforts must be valued as they keep the aesthetic standards from falling, and because they alone set the pace in taste.

there can be no doubt that our writing-printing-reading methods are antiquated and inefficient as compared to the perfection attained in other areas of human endeavor.

the history of our alphabet and any probing into its optical effectiveness expose a lack of principle and structure, precision and efficiency that should be evidenced in this important tool.

attempts have been made to design visually (to distinguish from aestheti-cally) improved alphabets. but redesigning will rest in just another typeface unless the design is primarily guided by optics as well as by a revision of spell-ing. this, in turn, reveals the need for a clearer relation of writing-printing to the spoken word, a reorganization of the alphabetic sound-symbols, the creation of new symbols. the type designer is not usually a language reformer, but a system-atic approach will inevitably carry him to a point where he will ask for nothing less than a complete overhaul of communication with visual sound.

however unlikely the possibilities for the adoption of such far-reaching renovation appears at the moment, revitalization of typography will come:

a. from the increased demands made on the psychophysiologic

apparatus of our perceptive senses;

b. from a new alphabet;

c. from the different physical forms that the carriers of typography will take. the more we read, the less we see. constant exposure to visual materials

has dulled our sense of seeing. overfed with reading as we are, the practice of reading must be activated. a new effort is needed to recapture and retain fresh-ness. little known is the fact that the act of seeing is work, that it demands more than a quarter of the nervous energy the human body burns up. during waking hours your eyes almost never rest. in reading this article you must refocus as you skip from word to word. much energy is required for blinking and turning the eyeballs. more is needed by the tiny ciliary muscles to alter the shape of the crystalline lens for focusing. the effort of seeing contributes a large share to physical tiredness.

taking a closer look at present-day typographic customs, i make the following suggestions, believing that they offer immediate possibilities for both improvement and change.

[ . . . ]

They called for clarity, conciseness, precision; for more articulation, contrast, tension in the color and black-and-white values of the typographic page.

UNIVERSAL COMMUNICATION

45

46

for a long time to come we will accept the existence of the different languages now in use. this will continue to pose barriers to communication, even after improved (possibly phonetic) writing methods have been adopted within all the languages. therefore, a more universal visual medium to bridge the gap between them must eventually evolve. first steps in this direction have, strangely enough, been made by the artist. now science must become a teammate and give him sup-port with precise methods for a more purposeful handling of visual problems.

the book has been a standard form for a long time. a new spirit invaded the stagnant field of rigidity with the adoption of the dynamic page composition. an important extension was introduced with the recognition of supranational picto-rial communication. with its combination of text and pictures, today’s magazine already represents a new standard medium. while pictorial communication in a new sense has lived through a short but inspiring childhood, typography has hardly aspired to become an integrated element.

exploration of the potentialities of the book of true text-picture integration has only begun and will, by itself, become of utmost importance to universal understanding.

Airplane.

SQUARE SPAN

tradition requires that sentences follow each other in a horizontal continuous sequence. paragraphs are used to ease perception by a slight break. there is

no reason for this to be the only method to transmit language to the eye. sentences could as well follow each other vertically or otherwise, if it would facilitate reading.

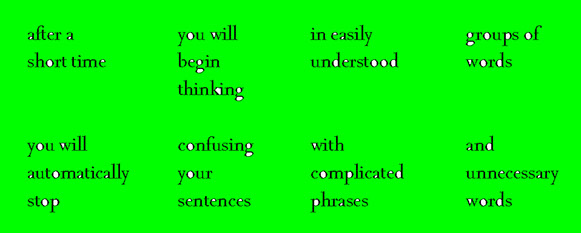

following is an excerpt of a letter from “the reporter of direct mail adver- tising”: “square span” is putting words into thought groups of two or three short lines, such as

My hometown.

typewriters and typesetting machines would have to be adjusted to this method. text written in logical, short thought groups lends itself best. the advantages of grouping words support the theory that we do not read individu-al letters, but words or phrases. this poses a new challenge for the typographer.

text in color black printing on white stock, because of its extreme opposites, is not entirely satisfactory. the eye forms complementary images. flickering and optical illusions occur, however minimized they may be in a small typeface. they can be reduced if the contrast of black on white is softened by gray printing on white stock; black printing on gray, yellow, light blue, or light green stock; brown, dark green, or dark blue printing on light colored stock. the colors of printing in relation to the colors of stock need not necessarily be chosen for harmonies; it is the power of controlled contrast that must be retained.

47

CHANGE OF IMPACT

furthermore, a great easing of reading is effected and freshness of perception is prolonged if a book is made up with a sequence of pages of different colored stock printed in various colors. which color follows another is less important than that the hues be approximately of equal value to safeguard continuity.

“square span” writing was developed by robert b. andrews, dallas, texas.

dr. w. h. bates has recommended a frequent shifting to aid in refocusing a fixed stare caused by the eye-tiring monotony of reading matter. the typographer can support this recommendation by the above change of impact through color.

(1) fragmented type panel and (2) photomontage and typomontage.

NEW SLAVES

Present indications are that this basic invention can be expected from the neighboring field of collotype. This process involves a machine that transfers the composed type-matter onto a film, and a printing machine that copies the negative onto sensitive paper. Thus the enormous weight of type and thebucket of ink disappear, and so here again we also have dematerialization. The most important aspect is that the production style for word and illustration is subject to one and the same process—to the collotype, to photography. Up to the present there has been no kind of representation as completely comprehensible to all people as photography. So we are faced with a book form in which representation is primary and the alphabet secondary.

In this way the automatism of the present-day book will be overcome;

into something that our minds can grasp as an organized unity.

48

speculation into the future (perhaps not so distant) leads me to assume that methods of communication will change drastically.

the storage of books will be replaced by microfilms, which in turn will change the design of libraries. computing machines can already substitute for printed matter by storing knowledge. they will have any and all desired information available and ready when needed on short call, faster, more completely than research teams could, relieving and unburdening our brains of memory ballast. this suggests that we will write and read less and less, and the book may be eliminated altogether. the time may come when we have learned to communicate by electronic or extrasensory means. . .

formalism and the straightjacket of a style lead to a dead end. the self-changing pulse of life is the nature of things with its unlimited forms and ways of expression. this we must recognize and not make new clichés out

of old formulas.

28

30

"ON TYPOGRAPHY ON TYPOGRAPHY "

Graphic design theory Graphic design theory Graphic design theory Graphic design theory Graphic design theory Graphic design theory

Herbert Bayer / 1967

"ON TYPOGRAPHY ON TYPOGRAPHY "

Graphic design theory Graphic design theory Graphic design theory Graphic design theory Graphic design theory Graphic design theory

Herbert Bayer / 1967